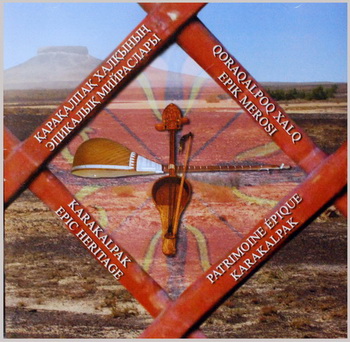

KARAKALPAK

EPIC HERITAGE

(free download CD in

mp3 format)

This

CD is dedicated to the living musical heritage

of the Karakalpak bards. It is the fruit of

a fieldwork inventory conducted in 2010 under

the auspices of UNESCO,* in cooperation with

cultural institutions from Uzbekistan and Karakalpakstan.

This inventory, which was conducted across the

entire region of Karakalpakstan, resulted in

the recording of nearly 300 vocal and instrumental

works. The 22 songs on this CD were selected

with the help of several well-known musicians,

including Qarimbay Tinibaev, the famous baqsi,

girdjek player and professor at the College

of Arts in Nukus, the capital of Karakalpakstan.

In

1936, Karakalpakstan became an autonomous republic

within Uzbekistan. It is situated in the Western

part of the country, between Kazakhstan in the

north and Turkmenistan in the south. Surrounded

by vast stretches of desert, where a continental

climate prevails, the Karakalpak epic heritage

has been transmitted by two key figures of this

culture: the jiraw and baqsi. The jiraw is a

bard specialized in heroic epics. He depicts

in his singing, the courage and strength of

heroes involved in titanic combats. His narrative

unfolds using a guttural tone and a deep voice

reminiscent of the sound of his two-string fiddle,

the qobiz. The voice and the fiddle of the jiraw,

as well as the content and values revealed in

his epics, convey the mythical world of the

nomads and the wild steppe of Central Asia.

As for the baqsi, his music stems from a rather

different style. He sings epic poems, which

instead celebrate courtly love, in a narrative

style that describes the quest for love, either

by an individual or a couple. The baqsi accompanies

himself with a two-string lute, the duwtar,

while singing in a natural voice. This tone

of voice, the lute and the subject matter of

the epics relate to the myths and dreams of

the sedentary societies of Central Asia. Therefore,

the musical culture of the Karakalpak bards

rests today on two traditions that are not mutually

exclusive, but rather complementary to each

other, specifically in regards to performance.

The epic is a narrative that lasts several hours,

and at times several nights. In the old days,

the baqsi or the jiraw were systematically invited

to weddings. Their performance was one of the

highlights of the ceremony. While the audience

gathered around the fire, the baqsi began by

loosening his fingers with pieces like Nama

basi (tracks 1, 20 and 21). Afterwards, he would

sing didactical and philosophical songs to warm

up his voice (tracks 5, 8 and 12). Once everyone

had gathered around, a venerable elder (aqsaqal)

would ask the audience which epic should be

sung. The aqsaqal would then recite a prayer

(patiya) before the start of the performance.

This occurred at a time when television, radio

and technological entertainments were not part

of everyday life. The narrative of the baqsi

was rather like a film projection. His voice

would bring all kinds of characters to life,

and then to their death—characters embroiled

in tumultuous adventures that enthralled his

audience, to the point of forgetting the passing

time. Each of these bards would devise his own

musical, narrative and gestural means in order

to sustain a lively performance, in the hope

that the listeners would laugh and cry.

The

bard has a very important status and role to

play in traditional Karakalpak society. He is

the bearer of a knowledge that has been passed

on from one generation to another; which has

three levels of transmission. First, he transmits

a cultural memory, which is historical and mythological

in nature. This memory nurtures a sense of belonging

and identity. Secondly, the bard possesses an

artistic body of knowledge that has been transmitted

to him by a master and to whom he will allude

all his life. These epics are articulated through

a distinctive musical aesthetic that was forged

by the great masters of the past (Aqymbet, Muwsa,

Suwej, Genjebaï…). And finally, his

role in society is to pass on moral and ethical

values to anyone listening to his singing. He

is an exemplary role model, not only for his

pupils who try to imitate him, but also for

the whole of his society, desirous to listen

to his voice and pay attention to his wisdom.

It

is obvious that the change that occurred in

the past decades, both technical and socio-cultural

significantly curtailed the social role of the

bards, as well as their spheres of expression.

Henceforth, the bard is subject to the time

constraints of concerts abroad, festivals and

competitions, as well as national commemorations,

during which their performances rarely exceed

ten minutes. Moreover, echoing the radical developments

that took place during the 20th century, today’s

bards are much less often solicited to perform

during weddings; they are rather replaced by

sound systems with many more decibels. As a

result, some musicians, along with their activities

as bards, mix traditional elements with pop

music. Others, however, put their “nose

to the grindstone,” in an effort to bring

back complete epics from old recordings (G.

Allambergenova, J. Piyazov). Nevertheless, the

number of registered students at the Nukus’

College of Arts, under the auspices of G. O’temuratov,

T. Qalliev, Q. Tinibaev or B. Sirimbetov, has

never been higher, since the college opened

in 1991. The interest of young people in the

work of the bard is undeniable, as is evidenced

by their participation in competitions, or in

the fieldwork inventory of 2010, during which

young bards could be recorded all over Karakalpakstan.

Thus, the release of this CD is a testimony

to the life of the Karakalpak epic traditions,

a tribute to the most influential bards of today,

and a support to young people who endeavor to

continue an ancient art of oral transmission,

which has endured the expanse of many centuries,

up to our present day.

Frederic

Leotar

Montreal, October 26, 2011

|

CD

in bouklet in PDF

(download)

1.

Nama basi, G’. O’temuratov,

duwtar, trad.

2.

Asirim, B. Sirimbetov, voice and qobiz,

trad.

3.

Ga’lga’lay, O. O’tambetov,

voice and duwtar (N. Nuratdinov, girdjek),

trad.

4.

Saltiq, G. Xamitova, voice and duwtar

(I. Sabourova, girdjek), trad.

5.

Begler, B. O’tepbergenov, voice

and duwtar, trad.

6.

Ulli ziban, J. Piyazov, voice and qobiz,

trad.

7.

Qoshim palwan, B. Asqarova, voice and

duwtar (I. Sabourova, girdjek), trad.

8.

Ken’esli ton, M. Aekeev, voice

and duwtar, trad.

9.

Kelte nalish, Z. Ibragimova, voice and

duwtar, trad.

10.

Idiris, N. Nuratdinov, voice and duwtar

(G. Sultamuratov, girdjek), trad.

11.

Qa’wender, M. Jumatova, voice

and duwtar, trad.

12.

Tolg’aw, B. Esemuratov, voice

and qobiz, trad.

13.

Neshe gu’ller, G. Ra’metova,

voice and duwtar

14.

Besperde, T. Qalliev, voice and duwtar

(S. Qayipnazarov, girdjek, A. Atarbaev,

balaman), trad.

15.

Sa’rbinaz, G. Allambergenova,

voice and duwtar (I. Sabourova, girdjek),

trad.

16.

Adin’nan, A. Seyilxanov, voice

and duwtar, trad.

17.

Sanali keldi, Z. Sheripova, voice and

duwtar, trad.

18.

Qu’nxoja, T. Qalliev, voice and

duwtar, trad.

19.

Muwsa sen yari, N. Nuratdinov, voice

and duwtar (G. Sultamuratov, girdjek),

trad.

20.

Qa’nigu’l, G. Allambergenova,

voice and duwtar (I. Sabourova, girdjek),

trad.

21.

Nalish, M. Jumatova, voice and duwtar,

trad.

22.

Aq ishik, G’. O’temuratov,

duwtar, trad.

|

|

This

project was carried out as part of a UNESCO

program entitled : “Strengthening

the implementation of the 2003 Convention

through National Inventory of living heritage

in selected region of Uzbekistan.”

|

|